My Father’s Shadow: The First Film That Made Me Cry

This write-up was drafted by Norman Busigu.

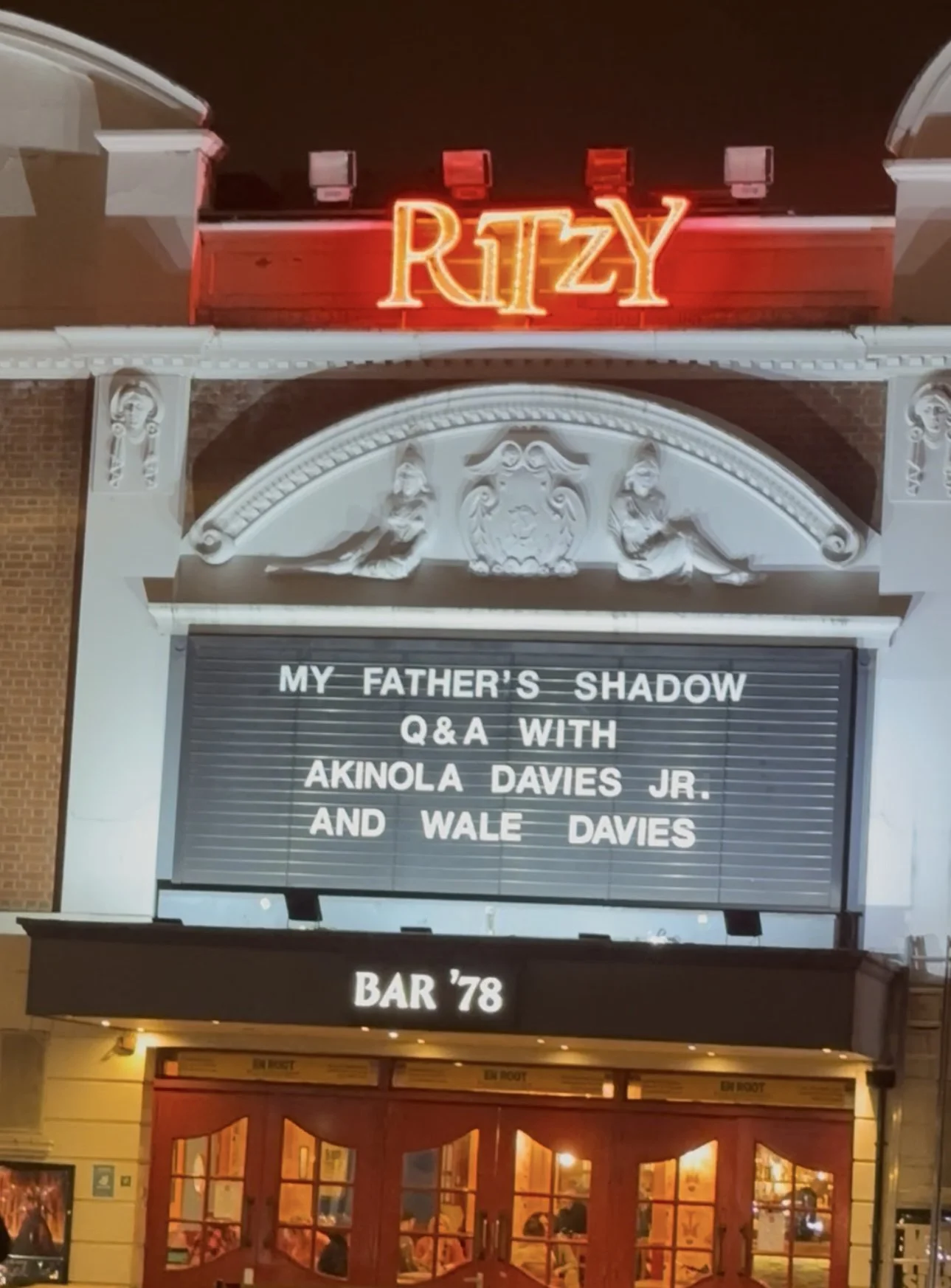

On 29th January 2026, I was invited by We Are Parable to a special UK screening of the Cannes Film Festival selected piece “My Father’s Shadow” at the Ritzy Cinema (Brixton), with a Q&A by director Akinola Davies Jr and writer Wale Davies thereafter. With a sold-out screening room and cinema-snacks to hand, the stage was set for a majestic night. The almost perfect blend of storytelling and acting created a realism so potent and prolific, that certain scenes reduced me to tears.

A New Frontier of African Storytelling Through Film

Set in 1993, this BAFTA nominated film takes place in Lagos, Nigeria during a significant transition point in its modern history. Lagos has long served as a major economic, industrial and cultural hub of Nigeria, and at large, West Africa. A film deeply seated within the socio-political context of the times, Nigeria of 1993 could be likened to a phoenix, aiming to emerge from the trappings of military rule and begin its course of democratic self-rule, and boldly become the Giant of Africa that it was long prophesised to be.

It is against this backdrop, that the writers Akinola and Wale masterfully capture intergenerational dialogue between the film’s protagonists (in a way few African films do) – two young brothers and their father – who we observe throughout the film trying to find their way amidst this city of dreams. From the weird and wonderful moment of a whale washing up on a beach shore… to the city being shutdown arbitrarily at a moment’s notice and menacingly flooded with military musclemen - we are given a window into this world: the chaos, the charisma, the creativity.

As someone who has previously made a film in Lagos, the magic and mystery of this city were both artistically and accurately captured in this motion picture. Akinola explained that he wanted to paint the picture of Lagos through the eyes of a child, and this is achieved poetically. It is showcased as a fun, vibrant and exciting city which is embracive of the intersections that co-exist, i.e. the Muslim/Christian communities, the disabled, rich/poor and everything in-between.

This melting pot of lived experiences are convincingly captured within the film through various means. The textures and aesthetics are warm and inviting, as are the colour schemes and fashions used to give us a glimpse into how the people stayed stylish (which they did). Rugged, yet refined. Raw, yet real. Radiant, yet restricted. This compounded with world class acting from the three key protagonists enables viewers to quickly build a relationship with the characters, who immediately feel more real than fictional.

Following The Follies of A Father And His Sons

Essentially, the story follows the journey of a father (Fola, played by Sope Dirisu) and his two sons (played by Godwin Chimerie Egbo and Chibuike Marvelous Egbo) enjoying the gift of a day – and this is the timeline across which the film takes place. A father who works in Lagos and has to frequently leave his wife and two sons, on this occasion decides to have his offspring accompany him to Lagos – after they plead with him not to leave them again.

We are a fly on the wall in their playful yet perilous journey to Lagos, as the two boys get a glimpse into the life their father leads. One early scene that stood out to me, was the three characters boarding a bus on their commute to Lagos. The warmth and welcoming by others on the bus for me humanised this everyday African experience in a way few films depicting African realism manage to pull off. From having his son hoisted on the lap of a stranger on a bus (and being accused of farting!), to then hitchhiking after said bus breaks down, we are entertained by the creativity displayed that is required to overcome the commonplace challenges of a system where the basic social infrastructure fail when needed most.

It is this can-do/find-a-way attitude which Africans have to practise on a daily basis, that the film really conveys authentically. Such scenes did not descend into an overly dramatic performance of navigating tragedy – rather the problems were tackled with humour and honesty. In between the laughs however, we could see the frustration that the average man faces, as the writers smoothly sprinkled in social commentary - for instance there being no car fuel for sale at a petrol station and concerns being raised of how people will even move their vehicles.

It is when the trio arrive to Lagos, where things the pace of the film increases and we learn more about the Fola, aka “Kapo”: the job he holds, the respect he commands, but (still a mortal man), how he still falls victim to the failings of his country. There is one scene firmly fixated in my mind of him at his workplace pleading for his salary, which is overdue by several months. He comes to learn that others have been waiting as long as 8 months for theirs. This scene pulled at my heartstrings - as he in real time learns the gravity of his situation - he worryingly glances over to his sons knowing he needs this money, now. His facial expression alone said over a thousand words.

While waiting for his supervisor to return, he is invited to explore Lagos with his sons to pass the time – and this is where the adventure arc of the film begins, as the trio find themselves in a series of miscellaneous mishaps and encounters. From seeing an old friends at a restaurant, to visiting the beach, to buying ice-cream, to later sitting in a bar. As each scene progresses, we observe poignant character development and gain insight into the intricate nature of how each character views the other. For instance, the resentment the youngest harbours towards his father for always being absent, while the older brother learns of his responsibilities as big bro, and how the death of his uncle resulted in him receiving his namesake.

The writers highlighted during the Q&A that they wanted to use the film as a conduit to explore certain existential themes that are seldom explored and openly discussed in our communities. Two of those being relationship between an African father and his children, and how Africans process death. Akinola and Wale expressed hope that these conversations will serve as a catalyst for change towards countering harmful traditional behaviours in our communities.

Managing the Realities of Military Rule

Where this film in my opinion truly shines is in its closing stages, where we are given the chance to explore the psyche of Nigerians, who eagerly await the announcement of the crucial 1993 elections. As it would turn out, during a live TV broadcast, the election results were annulled, crushing the dreams of those who placed hope in candidate M.K.O. (who represented positive change and a break into democracy that the masses yearned for). Once composed characters immediately descended into a spiral of mental turmoil, disbelief and despair as the news broke.

A nice nuanced touch I noticed, was the reference to Fela Kuti. As the individuals politicked amongst themselves where the country is going, one stated “demo-craze” – an ode to the Fela song Demo-Crazy (and the overarching sentiments of how western systems are literally driving Africans crazy). To see Kapo’s child-like belief that M.K.O would rightfully win vanish before our eyes and the psychological panic of an unknown future set in, is a story all too common for many Africans where electoral processes where allegations of rigging, ballot stuffing and censorship are common occurrences.

Shortly after this televised announcement, the city is put on high alert to prevent civil unrest, and the military are deployed. At this point, the trio hastily leave the bar and urgently scramble for the first taxi to get home. This marked a reality of how a normal day can transcend into absolute chaos. Not knowing if Kapo would make it out of the city alive (during a tense encountering with a power-warped soldier) - as his sons and others in the car watched on in horror not knowing what his fate would be - had me in tears and suspended in fear.

Emotive, Educational & Entertaining

As a member of the African diaspora, what made this movie so richly told was the authentic acting: the nuances and unique mannerisms in which the brothers would interact with each other, and their father. This attention to detail enables the film to translate the words on the script far beyond the screen. During the Q&A, the directors offered insight into the intensive process by which they selected the brothers. Choosing to opt for realism of actual brothers over a more Hollywood groomed media candidates, they stood true to the belief that you cannot fake familial bond.

This is not something that could have been executed if they had just sourced American or British actors. This demonstrates a commitment to investing in local talent, marking the next frontier of African films and storytelling being fulfilled, as the global north further integrates itself with the continent’s creative industry.

Throughout the film, wider rhetorical questions are presented for us to ponder on – from life, to love, and Africa’s liberation… Ironically, many of the challenges we see in 1993, are still present today. Some burning questions I’ve been left ruminating on since the rolling credits are: How much has really changed 33 years; when will the golden age of Africa and self-rule finally emerge; how will the trauma and collateral damaged experienced by generations in the interim ever be resolved, or at least, acknowledged? Just some food for thought…