Preserving and Propelling Post-Colonial East African Culture - Meet Dr. Anna Adima.

This interview was conducted and drafted by Norman Busigu.

In recent years, there has been something of a Afrocentrism renaissance happening in the global North, as felt across the spectrum of expressive mediums.

Dr. Anna Adima (Image supplied)

Allow me to provide two prominent examples. Music: the explosive rise of Afrobeats (fuelled by genre bending bops including “Essence”, “Calm Down”, and “Water”) have enabled our distinct sounds and rhythms to permeate into international soundscapes. Film: heartwarming blockbusters such as Queen of Katwe (which refreshingly offered a positive depiction of life in Africa and moved the needle beyond the traditional trope of poverty arising from the usual presentation of the place we call home) captured audiences imagination and hearts, to praise and acclaim.

While African culture is finally having its moment on the global stage, these advances are driven largely by the northern, southern and western regions. East Africa seemingly remains absent from these conversations, with few breakout stars and very little representation. Growing up in the UK as a British-Ugandan, it felt as if only long distance runners at the Olympics and marathons were our only export from the East that showcased the scope of our excellence and talent. Unfortunately, it would seem that in recent decades, the Eastern region of the continent has struggled to firmly stamp its mark and cement its position in the contemporary cultural landscape.

This said, Ugandan Writer, Researcher, Educator and cultural consultant Dr. Anna Adima has been steadfast in her mission to authentically shine a light on two particularly important aspects of post-colonial East across her portfolio of works. First, the role, lived experiences and contributions of women. And secondly, the ever evolving cultural landscape of the East African region. With there being an anthropological element to her prolific writings, Dr. Anna is chronicling modern history, whilst simultaneously paying homage to the pioneers of the past - some of whose stories have seldom been spotlighted.

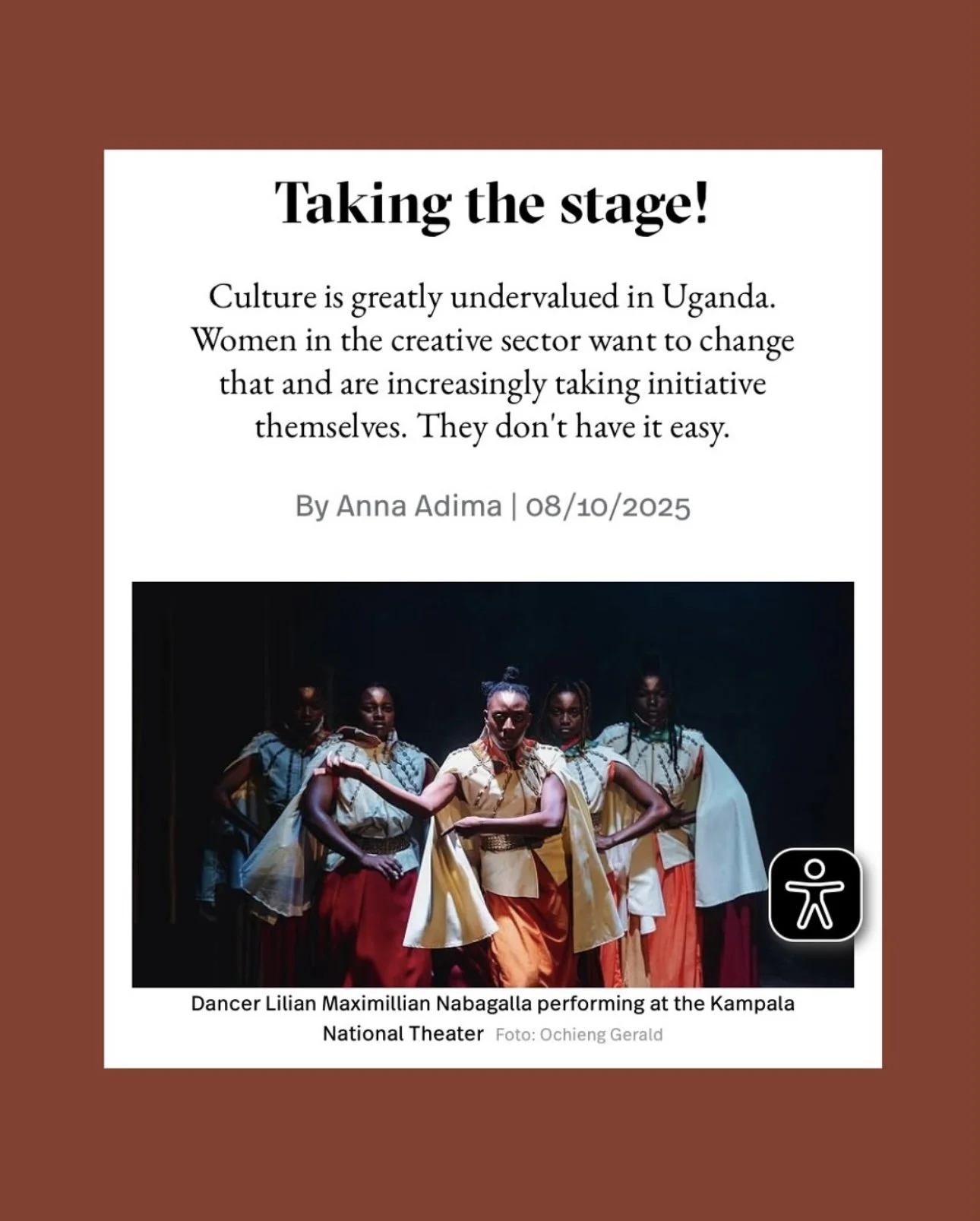

“KLA Writes, Day 2” - Kampala, Uganda (Image supplied)

At the time of writing this, Anna has just arrived in the UK to commence her role in teaching African History at Durham University. Before her tenure kicked off, we had some time to touch base: we sat down so that I could pick at her brains to explore her perspective on all of these themes in detail, and to learn more about her colourful life and journey.

***

1. Let’s start from the beginning – what initially drew your attention to becoming a writer? Further, when did you truly begin to understand the power of the pen – a potent medium to document stories and culture?

I’ve always loved reading (A fun fact about me: as a child, my mother used to punish me by forbidding me from reading!), and from an early age, I recognised the power of the written word in storytelling and worldbuilding. Writing, almost as an extension, almost came as second nature to me. In school, essay-based subjects, such as English and History were my best subjects, and I’ve always kept a diary on and off throughout my entire life. As an introvert who lives in her thoughts most of the time, I’ve found I express myself best through the written word, as in putting pen to paper, I can clarify the ideas that are jumbled in my head. There’s something about the written word that seems more enduring that other forms of media. It can last over decades, if not centuries, and stands the test of time, and there is a beauty in seeing words being re-read and re-interpreted across time and space. I think I only properly began to understand the potency of the written word, as a medium to document stories and culture, during my PhD research. I was reading the words of East African anti-colonial activists, writers and intellectuals and felt incredibly inspired – almost as if they were my contemporaries.

2. Two underlying themes I have noticed across your impressive portfolio of work is that you intentionally spotlight the lived experience of African women, and vividly explore the evolving cultural zeitgeist of post-colonial East Africa. What inspires you to ruminate on these topics so extensively and make them your areas of expertise?

There are two things, really. Firstly, my lived experience is that of an African woman. It is how I move about in the world and is a perspective that informs my reality. However, there is a disconnect between my experience and what I read about in history books. Mainstream histories frequently portray white, male perspectives, and if African or Black perspectives are included, these are often those of African men. However, African women are not a niche, as I constantly argue (I sound like a broken record to my students!). We make up fifty percent of the continent’s population – of course I would prioritise our experiences. I find the cultural landscape of post-colonial East Africa such a fascinating canvas for study. It was a period of vibrant artistic, cultural and literary production – the likes of which I don’t think the region has seen since the 1960s. Some of Africa’s best literary and artistic works were produced in that period in East Africa. At the same time, the 1960s were a decade that represented so much hope and optimism for independence. Every newspaper article, poem, novel, or play from this period that I have studied expresses the writer’s thoughts and ideals on this unique period. It is this hope that I find so beautiful to read about, and is something I return to when I feel pessimistic about the direction East African politics are taking today.

(Image supplied)

3. You have lived experience across Uganda, Germany and the UK – and (frequently) travel between these different realms. How has existing across Europe and Africa shaped your world view and affected your written abilities?

Living and moving in between different African and European countries from a young age has definitely given me a unique worldview, especially as a mixed-race Black woman. In East Africa (I say this, as I have lived in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania), I am afforded privileges as I am read as mzungu, while in Germany and Europe, I experience the effects of structural racism (of course, there are nuances to my experiences in both contexts). I am used to diving in and out of different cultures and linguistic contexts, which has given me a unique ability for empathy with individuals from different backgrounds. This ability to navigate between cultures seamlessly is what translates into my writing: I would like to think that I am quite quick at finding common ground for people reading my work around the world, and in showing the shared humanity across different cultures (not to sound all kumbaya!).

Growing up between different African and European countries has really shaped how I see the world, especially as a mixed-race Black woman. In East Africa (I’ve lived in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania), I’m often read as mzungu and treated with a certain level of privilege, while in Germany and elsewhere in Europe, I’m more directly confronted with structural racism (though, of course, my experiences in both places are complex and layered). Moving between cultures and languages has always been part of my life, and it’s made me comfortable navigating difference and relating to people from many backgrounds. And I fell this shows up in my writing: I try to meet readers where they are, find points of connection, and highlight what we share as humans across cultures (without getting too ‘kumbaya’ about it!).

4. Regarding your by-lines and/or (international) speaking engagements: what is your proudest accomplishment, and why?

I would say being in conversation with award-winning writer and novelist Jennifer Makumbi is definitely a career highlight. In June 2023, I got to chair a conversation with her in Kampala, and was blown away by her insight into and advice on becoming published as an African writer. One of her pieces of advice has remained with me to this day: don’t rush creative projects and take your time with them (as someone who likes quick wins, this was something I needed to hear!). Also, off stage, she is just one of the loveliest people you’ll ever meet. We had lunch together and she gifted me chocolate!

Dr. Anna Adima (Image supplied)

5. Who are your biggest inspirations in academia/literature?

Two people come to mind. One is Goretti Kyomuhendo, author of the recently published novel Promises. While I enjoy Kyomuhendo’s writing, and her ability to capture a contemporary Ugandan Zeitgeist, what makes her an inspiration is what she does for the literary community in Uganda and Africa. As the Founding Director of African Writers Trust, Kyomuhendo works tirelessly to promote the infrastructure to support literary production in Uganda, and also bridges the divide between writers on the continent and in the diaspora. Kyomuhendo also organises and curates some of the best literary events in Uganda, such as the recent Kampala Writes LitFest. Given the challenges of working in Uganda’s cultural sector, with lacking infrastructural support, Kyomuhendo’s ability to keep the country’s literary ecosystem alive is truly inspiring. Another inspiration is Dr Zaahida Nabagereka, currently Senior Social Impact Manager with Penguin Random House in the UK. As an expert in Ugandan and African literature, Zaahida works to make books accessible to marginalised communities, both in the UK and Uganda, making her an amazing role model for me.

6. You are now currently based in the UK, teaching African History at Durham University. Is there a particular chapter of African history (i.e. the Moors, the empire of Mansa Musa, Haile Selassie’s resistance to slavery etc) that you feel is significant but not widely known/spoken about? Also, which aspect of African history do you enjoy teaching the most?

That’s a good question! I think generally, African women’s histories still remain marginalised, both in academic and public history. It’s only in the past thirty years or so that we begin to see a shift in historical writing that is more inclusive towards African women. For example, looking at women’s perspectives of Mau Mau in colonial Kenya, or the Maji Maji uprising in Tanganyika, or under Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda: all of these are relatively new fields of study, and allow us to understand African histories in a different way. I enjoy teaching all aspects of African history (although, of course, I am biased towards East African history!) – however, if I had to choose, it would be topics that allow students to question standardised narratives of Africa as ‘backward’ or lagging behind. So, this might be courses on pre-colonial empires, African philosophies and knowledge systems, or African ideas of development.

7. Are you able to reflect on the transition from being a PhD student (studying under the tutelage of a professor/tutor) to now being a professional academic at Durham University, teaching your own students?

The transition is huge! Sometimes I still can’t believe that I’m in charge of a seminar group and that students look to me for advice! But I absolutely love teaching and it is one of my biggest passions, alongside writing. It’s a real privilege to contribute to shaping the minds of young people who will make the world a better place in their own ways. I learn so much from my students, and enjoy learning from their perspectives in seminar discussions and when reading their essays.

(Image supplied)

8. How would you describe the current state of Uganda’s creative industry? What do you think needs to happen for it to evolve and gain greater recognition on the African/global stage?

Uganda’s creative scene is buzzing. It’s vibrant and there is no lack of talent. I love hopping from one exhibition to the next, attending plays at the National Theatre, or going to a spoken word performance. However, if we’re talking about the industry, I would say that it is in its teen-stage. While talent is abundant, there is little opportunity to develop skill. And this is largely due to limitations in supportive infrastructure – education and training opportunities, professional development, and, of course, funding. Funding for the arts is almost non-existent in Uganda, and most arts projects are funded by smaller one-off grants from Western organisations. In terms of global recognition, I think restrictions on travel is one of the biggest impediments. The visa regulations of many countries in the Global North are so restrictive, that it prevents many Ugandan artists from travelling and networking with their contemporaries at an international level. But we’re getting there! In most creative sectors globally, we can think of one well-known Ugandan artist: Daniel Kaluuya, Joshua Baraka, or Jennifer Makumbi. However, for each Kaluuya, Baraka or Makumbi, there are a thousand others in Uganda carving out their skills within the limitations of existing infrastructure.

9. You are proud of Ugandan heritage and visibly show commitment to remain connected to home by passionately writing about Uganda/Africa - while helping to break down societal barriers which academia can cause. Why is this important to you?

Academia can be a space that reflects global inequalities and power dynamics – in terms of who produces and has access to knowledge. I feel that this knowledge should shared as equitably as possible across institutions and communities, in different formats, if we want to even begin to take a first step towards equity. I deeply love Uganda – for all its flaws (of which they are many!), it remains home, and there is nowhere on earth that I would rather be. And it is this love for Uganda that fuels my research and writing both within and outside of the academy. The world has so much to learn from Ugandan history – both the good and the bad – and I feel privileged to play a part in adding to knowledge on our country.

10. What role do you feel art plays in helping the African diaspora remain connected to countries they are from by heritage?

Arts plays one of the most pivotal roles in connecting the African diaspora to the continent. Take the example of literature and fiction. Reading stories and delving into realities different to one’s own helps build empathy and understanding for humanity. In the case of African diaspora communities, fiction by writers such as Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Abdulrazak Gurnah, or Leila Aboulela (who have recently written some excellent historical fiction) can help build an understanding of the continent and countries of their heritage. The shared cultural links can also help foster connection and build a picture of contemporary cultural discourse on the continent.

11. For anyone reading this who wishes to enter into the arena(s) of literature and academia as you have done across your portfolio career, what would your immediate advice be? What challenges did you experience when entering into these industries, and how did you overcome them?

Find a mentor and community! I cannot stress enough how important this is. Academia can be a brutal place – especially to Black women – and finding a mentor or someone with a few more years of experience under their belt who can advise you can be life-changing. It’s also important to build and maintain your community, both within and outside of the academy. I am lucky enough to have a few trusted friends and colleagues who I know I can turn to for support, advice, or even just a laugh at the end of a challenging week. I would also recommend being open to interdisciplinary research and diversifying your areas of expertise. The nature of the academic job market means that jobs in the humanities are increasingly scarce. I am able to market myself as both an historian and a literary scholar, which opens up a few more job opportunities than if I was solely either one or the other.

Dr. Anna Adima (Image supplied)